By Noam Rotstain

Abstract

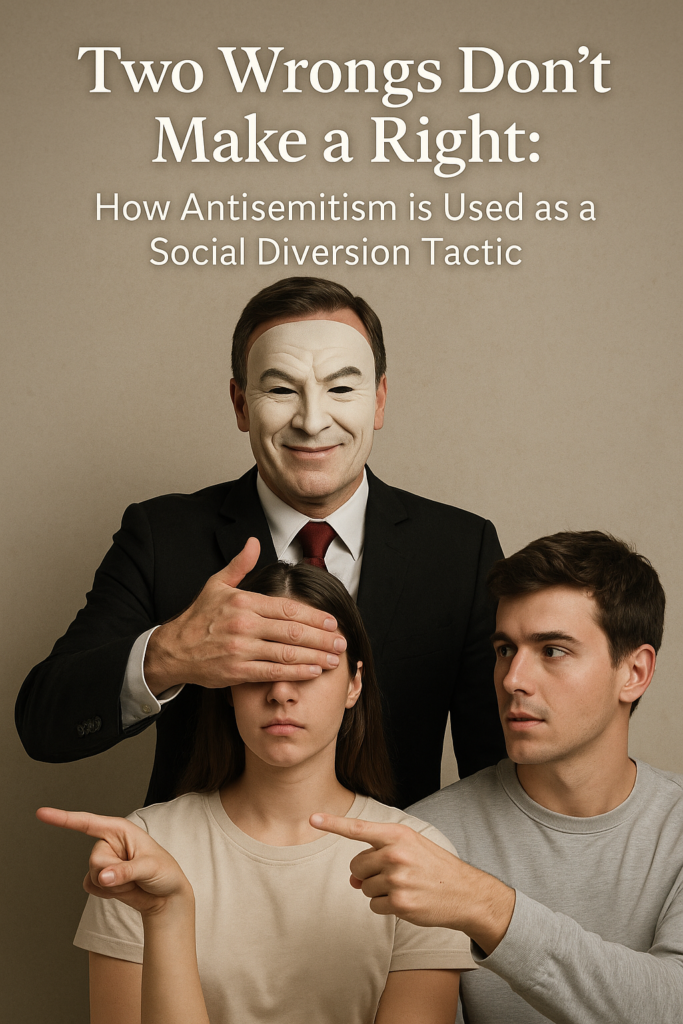

This paper investigates the resurgence of antisemitism, particularly in its modern guise of antizionism, as a strategic tool employed by political figures and institutions to deflect attention from internal crises, corruption, and institutional failures. Using South Africa, Spain, and International Criminal Court (ICC) Prosecutor Karim Khan as case studies, this research highlights how antisemitic rhetoric and disproportionate targeting of Israel serve as convenient scapegoats for political actors seeking to appease their constituencies, mask domestic shortcomings, and deflect international scrutiny. The paper argues that this misuse not only undermines legitimate human rights discourse but also emboldens antisemitism under the guise of social justice.

Research Question

How and why is modern antisemitism (especially in its antizionist form) used by political leaders and institutions as a diversionary tactic to shift public attention away from internal political, social, or ethical crises?

Introduction

Antisemitism, an enduring form of hatred, has taken on new forms in the 21st century, often masquerading as criticism of Israel or Zionism. While critique of Israeli policies is legitimate in democratic discourse, there is a growing pattern where such criticism crosses the line into antisemitism, particularly when it involves the demonization, delegitimization, or double standards applied to the Jewish state (IHRA, 2016). Increasingly, political actors leverage antizionist rhetoric not out of genuine concern for Palestinian rights but as a diversionary tactic to deflect from domestic crises. This paper explores this phenomenon through three case studies: South Africa, Spain, and the ICC’s Karim Khan.

Theoretical Framework

The analysis is grounded in several theoretical frameworks. First is the scapegoat theory (Girard, 1986), which explains how societal frustrations are projected onto an ‘other’ to create cohesion among the majority. Second is the concept of diversionary foreign policy (Levy, 1989), wherein leaders provoke or amplify foreign conflicts to unite their populace and distract from domestic failures. Finally, blame avoidance theory (Hood, 2011) explains how politicians strategically deflect accountability to maintain their credibility. Together, these frameworks provide a lens through which to understand how antisemitism and antizionism are repurposed as tools of political convenience.

Data and Trends

Global antisemitism reports reveal a disturbing correlation between domestic political instability and spikes in antisemitic incidents or rhetoric. According to the Anti-Defamation League (ADL, 2024), antisemitic incidents globally rose by 82% in 2023 compared to 2022. The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA, 2023) found that countries with increased far-left or far-right populist narratives often experience corresponding rises in antisemitic sentiment. In South Africa, reported antisemitic acts tripled during the ICJ case against Israel (SAJBD, 2024). Spain also saw a 60% increase in online antisemitism during its government’s recognition of Palestine (Observatorio de Antisemitismo, 2024). These data points underscore a global pattern: antisemitism is not only persistent but politically malleable.

Case Study: South Africa

Post-apartheid South Africa, long hailed for its democratic transition, has faced escalating crises in governance. The African National Congress (ANC), in power since 1994, has become embroiled in high-profile corruption scandals, most notably the “Phala Phala” affair, where President Ramaphosa was accused of concealing large sums of undeclared foreign currency found on his game farm (Daily Maverick, 2023).

Electricity blackouts, water shortages, and violent crime plague the nation. The unemployment rate hovers above 30%, with youth unemployment exceeding 60% (StatsSA, 2023). Discontent with ANC leadership has grown, and municipal elections reflect diminishing public trust.

Against this backdrop, South Africa spearheaded the 2024 ICJ genocide case against Israel, a move that aligned with pan-African and post-colonial solidarity narratives. Government ministers, particularly in the Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO), used highly emotive language, accusing Israel of apartheid, genocide, and ethnic cleansing. These claims, while resonant with certain activist circles, served as a smokescreen for the government’s growing domestic failures. Critics note that the ANC’s selective outrage fails to address ongoing violence in Sudan, Ethiopia, and other African contexts, suggesting a politically calculated focus on Israel to consolidate failing legitimacy at home while trying to grow social favourability through appealing to a social trend (Habib, 2023).

Case Study: Spain

Spain’s engagement with antisemitic rhetoric intensified in 2024 amidst a mounting political scandal involving Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez. His wife, Begoña Gómez, came under investigation for allegedly securing lucrative government contracts for private companies tied to her professional network (El Mundo, 2024). The scandal ignited a national crisis, prompting Sánchez to temporarily suspend public duties in a bid to reset his public image.

During this time, the Spanish government accelerated its campaign to recognize Palestinian statehood. Leading figures in the ruling coalition, including members of Podemos and other radical left parties, began issuing increasingly inflammatory statements comparing Israeli actions to Nazi Germany and apartheid South Africa. Media outlets and government-linked NGOs propagated narratives accusing Israel of genocide while downplaying or ignoring the rise of domestic antisemitic attacks (Observatorio de Antisemitismo, 2024).

This redirection of political discourse allowed Sánchez to reposition his administration as champions of human rights despite increasing domestic criticism over corruption, housing crises, and growing regional separatism in Catalonia and the Basque Country. These tactics mirror classic populist diversions—creating an external villain to unite fractured public opinion by attempting to use age-old antisemitic tactics (Mudde, 2007).

Case Study: ICC and Karim Khan

Karim Khan, elected as the ICC’s Chief Prosecutor in 2021, has struggled to maintain the institution’s legitimacy amidst accusations of Western bias and inaction on serious human rights abuses in non-Western countries. In 2024, Khan issued warrants against both Hamas leaders and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, drawing moral equivalence between a democratically elected leader and a terrorist organization.

This decision came as Khan himself faced multiple internal investigations. Leaked reports from ICC staff revealed allegations of sexual misconduct and coercion, as well as managerial abuse (Le Monde, 2024). Critics argue that Khan’s decision to target Israel was a strategic move to counter growing discontent within the Global South and within the ICC’s own ranks, where calls for prosecuting Western-aligned states have grown louder (Goldston, 2024).

The ICC’s track record also raises red flags: it has failed to indict leaders from countries like Syria, China, or Iran, despite voluminous evidence of state-led atrocities. By singling out Israel—a state with robust judicial review and democratic institutions—Khan appeared to be leveraging antizionist narratives to portray balance, deflect criticism, and reinforce the ICC’s contested legitimacy.

Comparative Analysis

Across these cases, a common mechanism emerges: antisemitism or exaggerated antizionism is wielded to redirect scrutiny, regain political capital, and mobilize emotional populism. In South Africa, it masks infrastructural collapse and unemployment. In Spain, it deflects from elite corruption. At the ICC, it functions as institutional self-preservation.

These actors rarely apply consistent human rights standards; rather, they select Israel as a symbolic antagonist to consolidate their own moral authority. This asymmetric application of outrage is not only politically dishonest but fundamentally erodes the credibility of international justice and democratic governance.

The Dangers of Normalizing Antisemitism

The normalization of antisemitism under the pretext of human rights advocacy sets a dangerous precedent. It distorts genuine calls for justice, alienates Jewish communities, and reduces complex geopolitical issues to simplistic moral binaries. Moreover, it opens the door for authoritarian regimes and corrupt officials to mask their failings behind a veil of virtue signaling. As recent scholarship warns, the misuse of moral outrage for political diversion undermines both minority protections and the democratic process (Marcus, 2022; Fine, 2020).

Policy Recommendations

To combat this trend, several measures must be implemented:

- Adopt and enforce the IHRA definition of antisemitism to differentiate between legitimate criticism and hate speech.

- Hold political and legal actors accountable for antisemitic rhetoric and diversionary tactics.

- Support independent media and civil society to expose manipulative narratives and refocus public attention on genuine governance challenges.

- Invest in public education to increase awareness of antisemitism’s evolving forms.

Conclusion

Antisemitism, when employed as a political strategy, constitutes not only a moral failure but also a threat to democratic accountability. As the case studies of South Africa, Spain, and Karim Khan demonstrate, antisemitism is increasingly being used to deflect from governance failures, scandals, and institutional decay. The international community must remain vigilant in identifying and calling out this exploitation, ensuring that the fight for justice does not become a mask for injustice.

References

Anti-Defamation League. (2024). Global antisemitism report. Daily Maverick. (2023). “The Phala Phala Scandal: Ramaphosa Under Fire.” El Mundo. (2024). “Investigación: La esposa del presidente y los contratos públicos.” European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2023). Antisemitism: Overview of data available in the European Union 2022. Fine, R. (2020). Antisemitism and the Left: On the Return of the Jewish Question. Manchester University Press.

Girard, R. (1986). The Scapegoat. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Goldston, J. A. (2024). “The ICC and Selective Justice: A Legal Critique.” Journal of International Criminal Justice, 22(2), 101–120.

Habib, A. (2023). “South Africa’s Foreign Policy and the Israel Question.” Foreign Affairs South Africa, 28(3), 56–70.

Hood, C. (2011). The Blame Game: Spin, Bureaucracy, and Self-Preservation in Government. Princeton University Press.

International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA). (2016). Working Definition of Antisemitism.

Le Monde. (2024). “Karim Khan: Enquête interne pour comportement inapproprié.”

Levy, J. S. (1989). “The Diversionary Theory of War.” The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 33(3), 292–313.

Marcus, K. (2022). The Definition of Anti-Semitism. Oxford University Press.

Msimang, S. (2023). “Failing Power, Failing State.” Daily Maverick.

Mudde, C. (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

Observatorio de Antisemitismo. (2024). Informe sobre antisemitismo en España.

South African Jewish Board of Deputies (SAJBD). (2024). Annual Antisemitism Report.